Antarctica

Keren Amattey & Damian Pang | 15 December 2021

A Continent of Extremes

Antarctica is a unique place. The icy world that covers the southernmost part of our planet is the coldest, driest, windiest, and highest continent on earth1: The lowest temperature ever recorded on our planet was -89.4˚C (-129˚F) on 21 July 1983 on the Soviet Vostok Station in Antarctica2; the average yearly precipitation is only around 50mm (2 in) when melted3; the cold, dry landmass creates katabatic winds that flow down from the high elevation interior towards the coast4, making Antarctica have the highest sustained wind speeds of any continent5; Antarctica’s average elevation is 2,200m (7,200ft) above sea level, making it it he highest continent6.

More than a Name

The word Antarctica simply means the opposite of the Arctic Circle or North Pole area (from Greek ant “against” and arktikos “of the north”7. Antarctica has long been a mystery since it was the last large landmass to be discovered on Earth. The 14,200,000 square kilometers of land8 sit at the far bottom of the Southern hemisphere. It is sparsely populated with only about 5,000 inhabitants in the summer—most of them research scientist and support staff—and reducing to just 1,000 in winter9. It’s not surprising because 98% of the region is covered in thick ice. Despite its ice cover, it is the driest and coldest place on Earth and considered a desert because how little rainfall it receives10.

History

The Mysterious Southern Continent

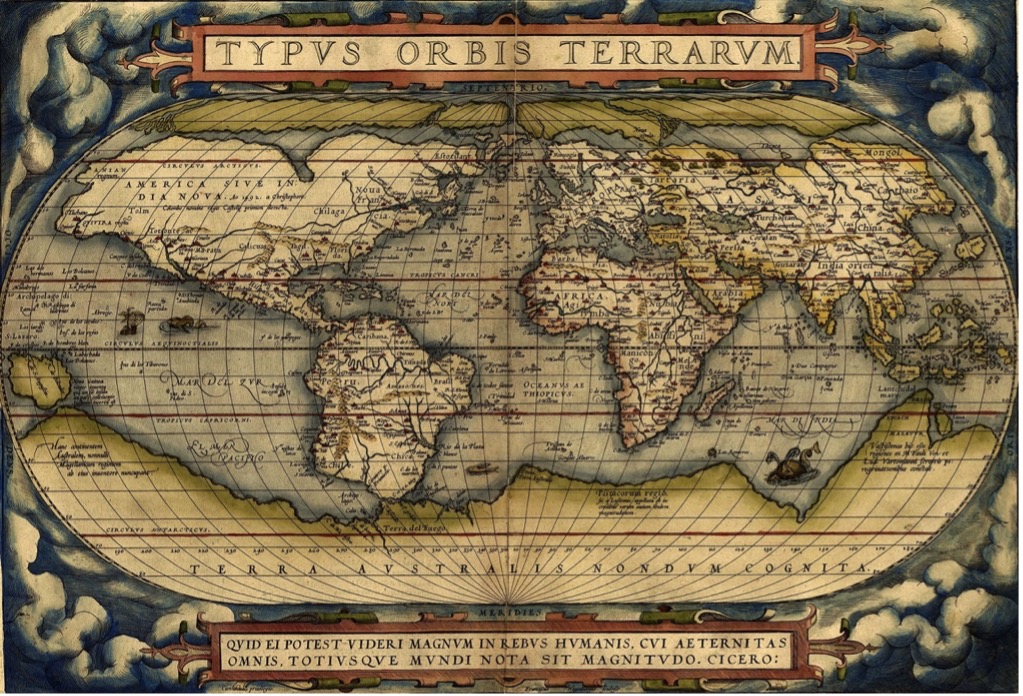

Explorers had a difficult time locating what is now known as Antarctica. As early as the second century BC, there were talks of the possibility of an undiscovered region in the southern hemisphere. Ptolemy, a mathematician and geographer, named it Terra Australis Incognita (“the Unknown Southern Land”). Aristotle said that due to the roundness of the earth, there must be a huge landmass in the southern hemisphere that balances out the land in the northern hemisphere11. And Shakespeare makes a character talk about keeping time with the Antipodes12, i.e. people on the opposite side of the world before either Australia or Antarctica were known to Europeans13. Many early geographers thought that it would be similar to other lands in the southern hemisphere and expected Antarctica to be huge, fertile and filled with riches. Early explorers of the Antarctic Circle were in for a big surprise!

Antarctic Exploration

The first person to cross into the Antarctic Circle in search of this unknown land was the British explorer and Navy officer James Cook and his crew in 177314. However, despite coming across islands close to the region, they did not see Antarctica itself. Cook was sure that no one would be able to travel as far South as he had. On their journey, they encountered icebergs with rocks embedded in them; proof that a more southerly land existed15. What Cook did not know was that, at one point during his search, he was just 120km away from the region16.

Many explorers braved the ice and the cold winds to be the first to lay eyes on this mysterious land, which finally happened in 1820 when a Russian expedition under the command of Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev spotted what is now known as the Fimbul Ice Shelf on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula17. They were unaware that a British ship was also in the vicinity trying to be the first to find this elusive continent. Irish captain Edward Bransfield saw the region just three days later18. However, von Bellingshausen’s accomplishment was hidden for decades because his journal was translated incorrectly19. In November, that same year, an American sealer called Nathaniel Palmer also caught sight of the region. Another American seal hunting vessel under the command of English-born American John Davis sighted the continent shortly after and recorded in the ships log of having gone ashore for an hour to look for seals, which would make them the first people to set foot on Antarctica in 182120, 21However, some historians have cast doubts on his claims, which would make seven men from the Norwegian whaling and sealing ship Antarctic (including Norwegians Henrik Johan Bull and New Zealander Alexander Francis Henry von Tunzelmann) the first to step onto the continent in 1895—their account being more widely accepted22. These early explorations sparked the race to the South Pole, which was first reached by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen23.

Who discovered Antarctica? That depends on what criteria are used. James Cook and his crew were the first to enter the Antarctic Circle and find evidence of land; von Bellingshausen and his crew were the first to set eyes on the continent; and either John Davis’ seal-hunting crew or that of the Norwegian ship Antarctic led by Henrik Johan Bull were the first to set foot on it.

Geography

Climate

Antarctica is by far the coldest region on the planet: It holds the record for the lowest temperature ever recorded on our planet (-89.4˚C/-129˚F)24 and is the only continent where most areas are below freezing all year long25. Despite being covered in thick ice and snow26, yet it is an extremely dry place with an average yearly precipitation of only 50mm (2 in) when melted27. It is also the windiest continent28.

Physical Features

Antarctica’s land area covers about 14.2 million sq km (5.5 million sq miles)29 but its ice sheet swells up to over 19 million sq km (7.3 million sq miles) in winter30. This makes it the fifth largest continent in the world, taking up about 20% of all land in the Southern hemisphere31. The continent’s main feature are its ice shelves that can grow to almost 5km (3 miles) in thickness32 and mountains. 98% of its landmass is covered in the world’s largest single piece of ice33, 34 Unlike the Artic in the North, Antarctica has solid bedrock underneath the ice35. On its edges, ice shelves extend into the sea and break away at the coast, drifting off as icebergs36 as the glacial moves from the interior outwards at rates between 10 to 1,000 m (33- 32,800 ft) per year37. The rugged terrain underneath the ice rises into large summits within multiple mountain ranges, some reaching over 4,500 m (14,800 ft)38. Even away from the peaks, the terrain and the ice sheet above reach an average elevation of 2,200m (7,200ft) above sea level, higher than any other continent39.

Biodiversity

Little vegetation survives on this icy continent. There are only some lichens, mosses, and terrestrial algae that grow on it, mostly in the northern and coastal regions40. But marine life flourishes: Nutrient-rich upwellings help phytoplankton and algae to thrive, which supports other small organisms like krill41. An estimated 500 million tons of krill live in the Southern Ocean, making it the most abundant animal in the world and providing the basis for many other species—from squids and fish to birds, penguins, seals and whales42. While many marine mammals like humpbacks, minkes, sperm whales, and blue whales have healthy populations in the region43, there are no proper land mammals, reptiles, or amphibians on the continent44. Humans have introduced some terrestrial animals to subantarctic areas but the main continent is still largely free of land animals45. However, many birds, seals, and penguins inhabit the land. An estimated 20 million penguins live on Antarctica’s shores46.

People, Economy, Culture, and Cuisine

Antarctica is home to only a few thousand scientist and support staff; most of them are only visiting during the summer months with only a skeleton crew remaining during the winter47. There is no native population and hence, no native culture or cuisine48. The population is around 4,400 in the summer and 1,100 in the winter plus around 1,000 more stationed on research ships close by49. Economic output is primarily in the form of research but no official economic data exist and given the small population, it would likely be very small.

Politics

In 1959, twelve countries who had scientist in the southern polar area signed the Antarctic Treaty and many more have since ratified it, bringing the total number of signatory countries to 5450. The treaty recognizes that no one owns the land and gives everyone the freedom to conduct scientific research and for peaceful purposes only.

About the Author

Keren Amattey is a geographer from Ghana. She studied Political Science and Geography at the University of Ghana. She loves reading about the world’s issues and every other romance book she can find.

1 LearNZ. (n.d.). Antarctica. LearNZ. URL: https://www.learnz.org.nz/scienceonice144/antarctica

2 Krause, P F., & Flood, K. L. (1997). Weather and Climate Extremes. Alexandria, VA: US Army Corps of Engineers Topographic Engineering Center.

3 Watt, L. van der (2021). Antarctica. Encyclopedia Britannica. URL: https://www.britannica.com/place/Antarctica

4 Editors of the Encyclopaedia. (2020). Katabatic wind. Encyclopedia Britannica. URL: https://www.britannica.com/science/katabatic-wind

5 American Museum of Natural History. (n.d.). Katabatic winds. American Museum of Natural History. URL: https://www.amnh.org/learn-teach/curriculum-collections/antarctica/extreme-winds/katabatic-winds

6 Watt, L. van der (2021). Antarctica. Encyclopedia Britannica. URL: https://www.britannica.com/place/Antarctica

7 Harper, D. (n.d.). Etymology of antarctic. Online Etymology Dictionary. URL: https://www.etymonline.com/word/antarctic

8 Central Intelligence Agency. (2021). Antarctica. World Fact Book. URL: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/antarctica/

9 Central Intelligence Agency. (2021). Antarctica. World Fact Book. URL: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/antarctica/

10 Central Intelligence Agency. (2021). Antarctica. World Fact Book. URL: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/antarctica/

11 Aristotle (ca. 350 BCE/1923) Meteorologica. Book II, Part 5 (Translated by E. Webster). Oxford, UK: Clarendon. P.140.

12 Shakespeare, W. (1600/2009). The Merchant of Venice, 5.1.127-128. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

13 Delaney, J. (2010). Terra Australis. Strait through: Magellan to Cook & the Pacific. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Library. URL: https://lib-dbserver.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/pacific/pacific-ocean/terra-australis.html

14 Cook, James (2003). Philip Edwards(ed). The Journals of Cook. Penguin Books. p. 250. ISBN 978-0141928081

15 Cook, James (2003). Philip Edwards(ed). The Journals of Cook. Penguin Books. p. 250. ISBN 978-0141928081

16 Cook, James (2003). Philip Edwards(ed). The Journals of Cook. Penguin Books. p. 250. ISBN 978-0141928081

17 Armstrong, T. E. (1971). The “Bellingshausen and the discovery of Antarctica”. Polar Record, 15(99), 887-889. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247400062112

18 Blakemore, E. (2020, Jan 27). Who really discovered Antarctica? Depends who you ask. National Geographic. URL: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/who-discovered-antarctica-depends-who-ask

19 Blakemore, E. (2020, Jan 27). Who really discovered Antarctica? Depends who you ask. National Geographic. URL: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/who-discovered-antarctica-depends-who-ask

20 Stackpole, E. A. (1935). The voyage of the Huron and the Huntress: The American Sealers and the discovery of the continent of Antarctica. Mystic, CT: Marine Historical Association.

21 Blakemore, E. (2020, Jan 27). Who really discovered Antarctica? Depends who you ask. National Geographic. URL: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/who-discovered-antarctica-depends-who-ask

22 New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. (2021). First landing on Antarctica. New Zealand History. URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/first-landing-antarctica

23 Blakemore, E. (2020, Jan 27). Who really discovered Antarctica? Depends who you ask. National Geographic. URL: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/who-discovered-antarctica-depends-who-ask

24 Krause, P F., & Flood, K. L. (1997). Weather and Climate Extremes. Alexandria, VA: US Army Corps of Engineers Topographic Engineering Center.

25 Boyall, L. (2021). Physical geography of Antarctica. Antarctic Glaciers. URL: http://www.antarcticglaciers.org/antarctica-2/introductory-antarctic-resources/an-introduction-to-antarctica/

26 Boyall, L. (2021). Physical geography of Antarctica. Antarctic Glaciers. URL: http://www.antarcticglaciers.org/antarctica-2/introductory-antarctic-resources/an-introduction-to-antarctica/

27 Watt, L. van der (2021). Antarctica. Encyclopedia Britannica. URL: https://www.britannica.com/place/Antarctica

28 American Museum of Natural History. (n.d.). Katabatic winds. American Museum of Natural History. URL: https://www.amnh.org/learn-teach/curriculum-collections/antarctica/extreme-winds/katabatic-winds

29 Central Intelligence Agency. (2021). Antarctica. World Fact Book. URL: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/antarctica/

30 National Geographic Society. (2012). Antarctica. National Geographic. URL:https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/antarctica/

31 National Geographic Society (2012). Antarctica. National Geographic. URL:https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/antarctica/

32 NASA https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/icebridge/multimedia/fall11/antarctica-US.html

33 Boyall, L. (2021). Physical geography of Antarctica. Antarctic Glaciers. URL: http://www.antarcticglaciers.org/antarctica-2/introductory-antarctic-resources/an-introduction-to-antarctica/

34 National Geographic Society. (2012). Antarctica. National Geographic. URL:https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/antarctica/

35 Boyall, L. (2021). Physical geography of Antarctica. Antarctic Glaciers. URL: http://www.antarcticglaciers.org/antarctica-2/introductory-antarctic-resources/an-introduction-to-antarctica/

36 Australian Government. (2020). Antarctic geography. Australian Antarctic Program. URL: https://www.antarctica.gov.au/about-antarctica/geography-and-geology/geography/

37 National Geographic Society. (2012). Antarctica. National Geographic. URL:https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/antarctica/

38 National Geographic Society. (2012). Antarctica. National Geographic. URL:https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/antarctica/

39 Watt, L. van der (2021). Antarctica. Encyclopedia Britannica. URL: https://www.britannica.com/place/Antarctica

40 National Geographic Society. (2012). Antarctica. National Geographic. URL:https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/antarctica/

41 National Geographic Society. (2012). Antarctica. National Geographic. URL:https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/antarctica/

42 Ice Stories. (2015 Antarctic marine ecosystems. Exploratorium. URL: http://icestories.exploratorium.edu/dispatches/big-ideas/antarctic-ecosystem-marine/index.html

43 National Geographic Society. (2012). Antarctica. National Geographic. URL:https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/antarctica/

44 Natural Environment Research Council. (2015). Land animals. British Antarctic Survey. URL: https://www.bas.ac.uk/about/antarctica/wildlife/land-animals/

45 Natural Environment Research Council. (2015). Land animals. British Antarctic Survey. URL: https://www.bas.ac.uk/about/antarctica/wildlife/land-animals/

46 BAS. (2015). Penguins. British Antarctic Survey. URL: ttps://www.bas.ac.uk/about/antarctica/wildlife/penguins/

47 Central Intelligence Agency. (2021). Antarctica. World Fact Book. URL: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/antarctica/

48 Central Intelligence Agency. (2021). Antarctica. World Fact Book. URL: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/antarctica/

49 Central Intelligence Agency. (2021). Antarctica. World Fact Book. URL: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/antarctica/

50 Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty. (2021). The Antarctic Treaty. URL: https://www.ats.aq/e/antarctictreaty.html