Sunspots

What Are Sunspots?

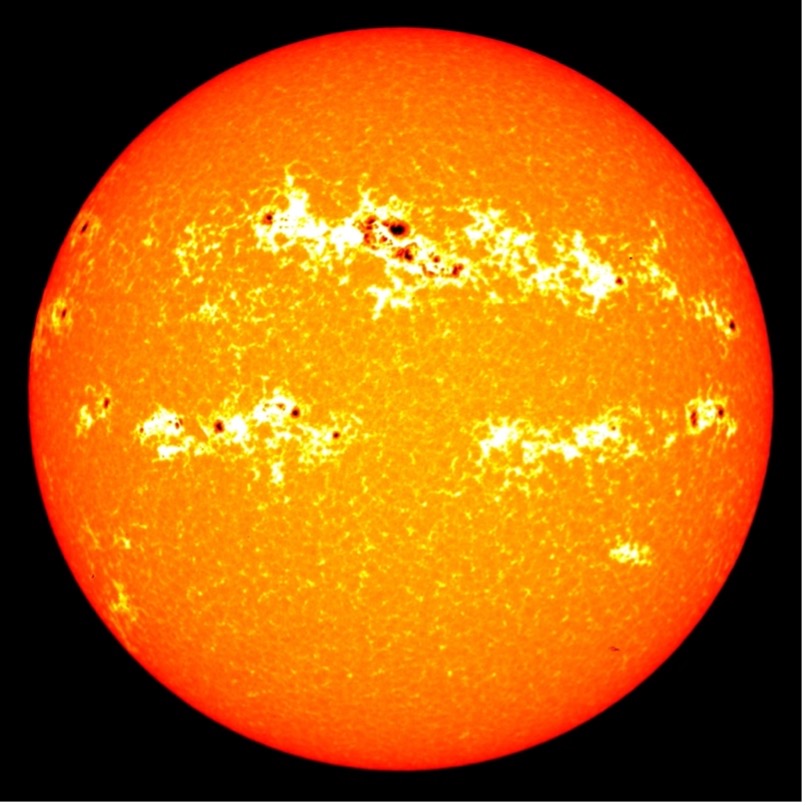

Sunspots are areas that appear as dark patches on the Sun’s surface[1]. Magnetic fields are common in stars[2] and our Sun is no exception to this[3]. Intense local magnetic activity a thousand times stronger than Earth’s magnetic field[4] can stop hot gas from reaching the solar surface and result in regions that are up to 2,800˚C (5,000˚F) cooler than their surroundings[5], which makes them appear as darker spots. Most sunspots come in pairs, often with opposite magnetic polarity (one having a positive and the other having a negative magnetic field)[6]. Although cooler than the rest of the Sun’s surface, they are still incredibly hot with most still reaching temperatures well above 2,500˚C (4,500˚F). Sunspots are not just on the surface but can reach up to 1,000 km (600 miles) deep into the Sun’s interior[7].

Dynamic Changes

The surface of the Sun is in constant flux and changes rapidly. Sunspots form and fade relatively fast and usually last for a few days, although very large ones can persist for several weeks[8] or even months while very small ones may fade after a few hours[9]. Sunspots are typically between 1,500km-50,000km in diameter[10] but some can be far bigger than that! Astronomers measure them as fractions of the Sun’s visible hemisphere, usually in millionths (1/1,000,000) or msh for short[11]. When using this measurement, the Earth only measures 169msh while large sunspots can easily measure 300-500msh[12] and some are visible to the naked eye (with proper protective filters). The largest ever recorded sunspot occurred in 1947 (often referred to as the Great Sunspot of 1947) and measured 6,132msh[13]. At its peak, the sunspot group reached a length of 376,00km, over two and a half times the size of Jupiter[14]!

Anatomy of Sunspots

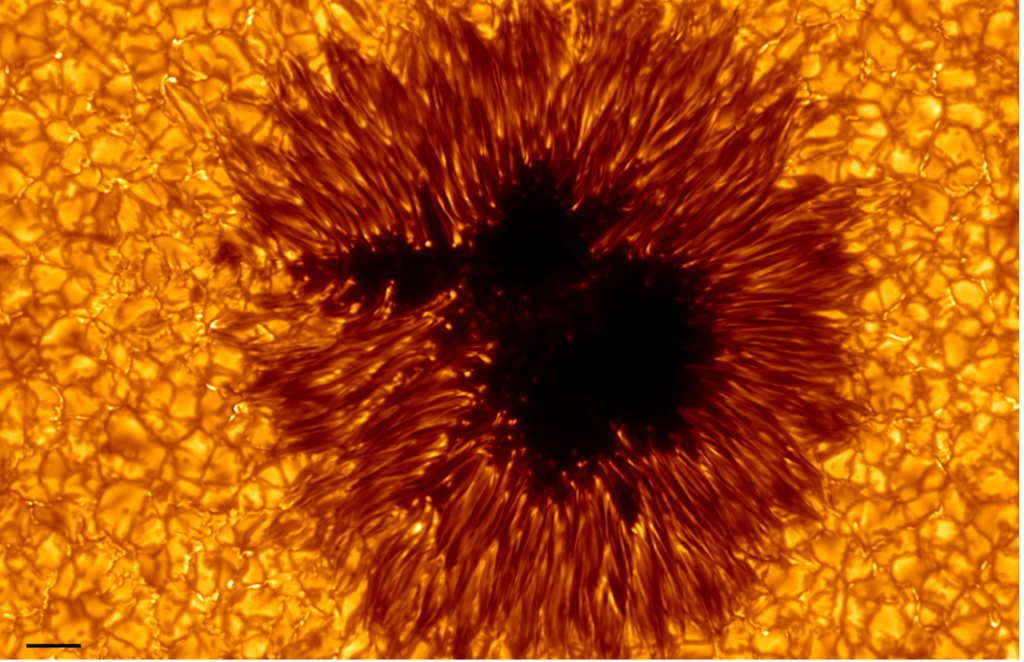

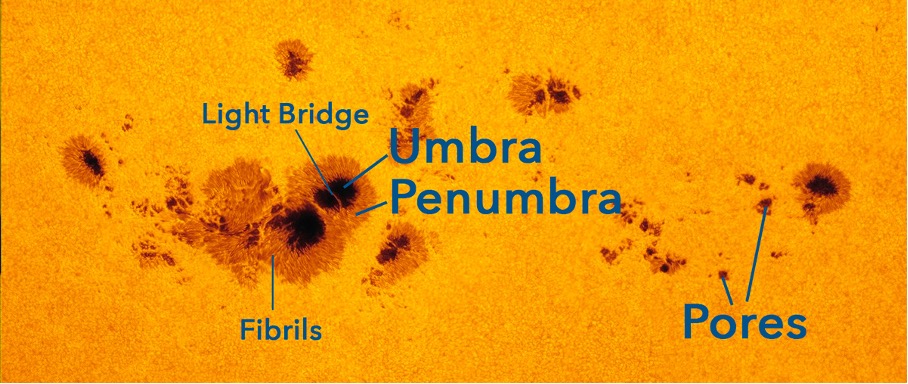

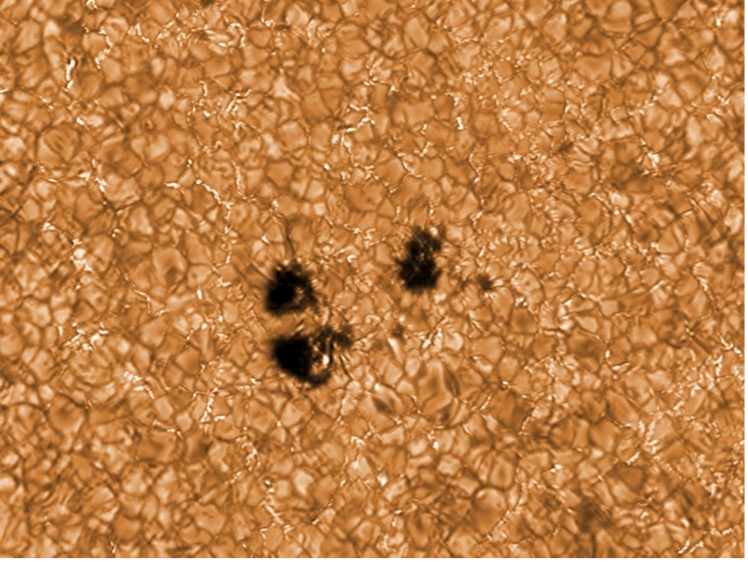

Sunspots have two parts: The inner, darker looking part is called the umbra and is cooler, with temperatures around 2,500˚C (4,500˚F) [15]. The outer part is called the penumbra and has temperatures that can reach 3,500˚C (6,300˚F)[16]. The outer penumbra often consists of streaky filaments called fibrils[17]. “Naked” sunspots without a penumbra are called pores and are usually smaller (1’000km-6,000km in diameter)[18]. Pores often have smaller bright areas inside them, which show that they do not fully supress heat transfer from below[19].

At times, brighter areas cut across a sunspot, dividing the umbra or pore into smaller areas. These structures are called light bridges[20] and they form when magnetic field lines form a type of canopy where the magnetic field strength is less than in the surrounding umbra[21].

The surface of sunspots is lower than the surrounding areas by about 500-700km and is known as the Wilson depression[22].

History

Ancient European observers believed that the heavens were perfect, which made them rule out even the possibility of any imperfections on the sun. Dark spots were explained away as transits of planets like Mercury or Venus[23]. Ancient Chinese astronomers did not have this presupposition and the earliest known mention of sunspots were by Gan De in the fourth century BC[24]. In 165 BC, a Chinese encyclopaedia called “The Ocean of Jade” described how the Chinese character wang appeared in the sun, which some now see as the first precisely dated sunspot in the historical record[25]. Systematic records of sunspots survive in the official imperial histories of China starting in 28 BC—although this may have started earlier as most records prior to this date have been lost[26]. In the West, the earliest clear reference to sunspots was made in Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne (around 807 AD) [27]. The Islamic scholars Abu al_Fadl Ja’far ibn al-Muqtafi wrote about sunspots in 840 AD and Ibn Rushd in 1196[28].

The English monk John of Worcester (who likely died in 1140) provided the first known drawing of sunspots in 1128[29]. Detailed observations and recordings of sunspots started with the invention of the telescope, which were pioneered by the English astronomer Thomas Harriot in 1610 but it was the observations by the German pastor and astronomer David Fabricius and his son Johannes in 1611 that led to the first scientific publication on the topic (penned by Johannes Fabricius)[30]. Others spotted sunspots independently around the same time, including Galileo Galilei in Italy and the German Jesuit Christoph Scheiner[31]. Sunspot records are among the longest directly recorded scientific data series, spanning over 400 years[32]!

Summary

Sunspots are local areas that are cooler than the rest of the Sun’s surface and appear as dark spots. They form and disappear relatively quickly, with smaller ones only lasting a few hours while large ones can persist for a few months. Sunspots are the result of strong local magnetism that prevents some heat being transferred from below. Surrounding the inner dark spot called the umbra is an intermediate area called the penumbra that consists of long filaments called fibrils. Small sunspots without a penumbra are called pores. Sunspots can be gigantic with the largest recorded group being well over twice the size of Jupiter! Ancient Chinese manuscripts mention sunspots almost 2500 years ago and detailed. Detailed observations and records started in 1610, providing one of the longest continuous scientific data series.

[1] Morgan, B., et al., (2014). The planets: The definitive visual guide to our solar system. London, UK: DK.

[2] Stello, D., Cantiello, M., Fuller, J., Huber, D., García, R. A., Bedding, T. R., … & Aguirre, V. S. (2016). A prevalence of dynamo-generated magnetic fields in the cores of intermediate-mass stars. Nature, 529(7586), 364-367. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16171

[3] Howell, E. (2019). Surprise! Sun’s Magnetic Field Is Stronger Than We Thought. Space. URL: https://www.space.com/scientists-measure-solar-magnetic-field-flare.html

[4] Hathaway, D. H. (2014). Photospheric features. Solar Physics: Marshall Space Flight Center. Huntsville, AL: NASA (Marshall Space Flight Center). URL: https://solarscience.msfc.nasa.gov/feature1.shtml

[5] Stott, C., Dinwiddie, R., Hughes, D. & Sparrow, G. (2010). Space: From earth to the edge of the universe. London, UK: DK.

[6] Hathaway, D. H. (2014). Photospheric features. Solar Physics: Marshall Space Flight Center. Huntsville, AL: NASA (Marshall Space Flight Center). URL: https://solarscience.msfc.nasa.gov/feature1.shtml

[7] Stott, C., Dinwiddie, R., Hughes, D. & Sparrow, G. (2010). Space: From earth to the edge of the universe. London, UK: DK.

[8] Hathaway, D. H. (2014). Photospheric features. Solar Physics: Marshall Space Flight Center. Huntsville, AL: NASA (Marshall Space Flight Center). URL: https://solarscience.msfc.nasa.gov/feature1.shtml

[9] Stott, C., Dinwiddie, R., Hughes, D. & Sparrow, G. (2010). Space: From earth to the edge of the universe. London, UK: DK.

[10] Stott, C., Dinwiddie, R., Hughes, D. & Sparrow, G. (2010). Space: From earth to the edge of the universe. London, UK: DK.

[11] SpaceWeather.Com. (n.d.). History’s biggest sunspots. SpaceWeather. URL: https://spaceweather.com/sunspots/history.html

[12] SpaceWeather.Com. (n.d.). History’s biggest sunspots. SpaceWeather. URL: https://spaceweather.com/sunspots/history.html

[13] SpaceWeather.Com. (n.d.). History’s biggest sunspots. SpaceWeather. URL: https://spaceweather.com/sunspots/history.html

[14] Meadows, P. (2021). The five greatest sunspot groups. British Astronomical Association. URL: https://britastro.org/journal_contents_ite/the-five-greatest-sunspot-groups

[15] Morgan, B., et al., (2014). The planets: The definitive visual guide to our solar system. London, UK: DK.

[16] Morgan, B., et al., (2014). The planets: The definitive visual guide to our solar system. London, UK: DK.

[17] Morgan, B., et al., (2014). The planets: The definitive visual guide to our solar system. London, UK: DK.

[18] Sobotka, M. (2020). Solar Pores. European Solar Telescope. URL: https://est-east.eu/?option=com_content&view=article&id=797&lang=en&Itemid=622

[19] Sobotka, M. (2020). Solar Pores. EST. URL: https://est-east.eu/?option=com_content&view=article&id=797&lang=en&Itemid=622

[20] Toriumi, S., Katsukawa, Y., & Cheung, M. C. (2015). Light bridge in a developing active region. I. Observation of light bridge and its dynamic activity phenomena. The Astrophysical Journal, 811(2), 137. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/811/2/137

[21] Felipe, T., Collados, M., Khomenko, E., Kuckein, C., Ramos, A. A., Balthasar, H., … & Waldmann, T. (2016). Three-dimensional structure of a sunspot light bridge. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 596, A59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201629586

[22] Löptien, B. (2018). Wilson depression in sunspots. Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research. URL: https://www.mps.mpg.de/5742487/wilson-depression

[23] Temple, R. K. G. (1988). The observation of sunspots. The UNESCO Courier, XLI(10), p. 9.

[24] Temple, R. K. G. (1988). The observation of sunspots. The UNESCO Courier, XLI(10), p. 9.

[25] Temple, R. K. G. (1988). The observation of sunspots. The UNESCO Courier, XLI(10), p. 9.

[26] Temple, R. K. G. (1988). The observation of sunspots. The UNESCO Courier, XLI(10), p. 9.

[27] Temple, R. K. G. (1988). The observation of sunspots. The UNESCO Courier, XLI(10), p. 9.

[28] Temple, R. K. G. (1988). The observation of sunspots. The UNESCO Courier, XLI(10), p. 9.

[29] Blyth, J. (n.d.). Th illustrations of John of Worcester’s Chronicle of England. Corpus Christi College Oxford. URL: https://www.ccc.ox.ac.uk/illustrations-john-worcesters-chronicle-england-ccc-ms-157

[30] Fox, K. C. (2011). Celebrating 400 years of sunspot observations. NASA. URL: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/news/400yrs-spots.html

[31] Fox, K. C. (2011). Celebrating 400 years of sunspot observations. NASA. URL: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/news/400yrs-spots.html

[32] Usoskin, I. G., Mursula, K., Arlt, R., & Kovaltsov, G. A. (2009). A solar cycle lost in 1793–1800: early sunspot observations resolve the old mystery. The Astrophysical Journal, 700(2), L154. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/700/2/L154