The Historic Conception of Continents

The Origins of Continents

Ancient Greek seafarers divided their world into two parts as a means for navigation: Europe to the west of the Aegean Sea and Asia to the east[i]. Over time, this division was extended through the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara, and through the Bosporus all the way to the Sea of Azov[ii] (shown in Image 1). Ancient Greek philosophers expanded this maritime division into a general worldview where the land of their world was divided into two great landmasses[iii]. Libya—the land west of the Nile—was later added as a third continent and loosely represents at least the northern part of Africa[iv].

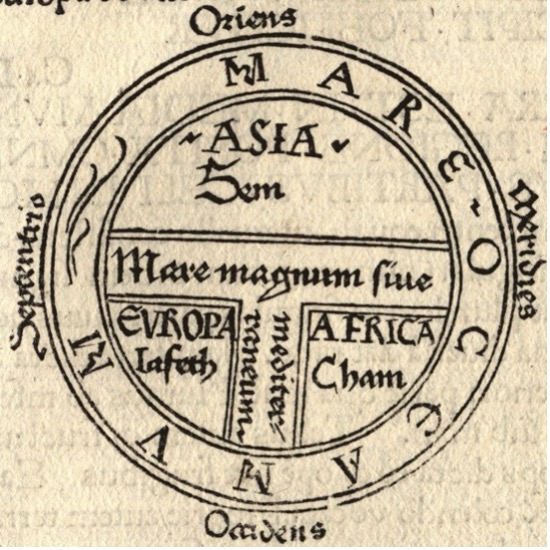

This threefold division fit neatly with the Greek believe of a perfectly ordered world with an elegant geometry[v] and survived for over 2’000 years! Although the ancient Greeks produced relatively accurate maps of the Mediterranean region starting with Anaximander of Miletus (ca. 610-546 BCE)[vi] and culminating in the work of Claudius Ptolemy (ca. 90-168 CE)[vii], the geometric three-part view persisted as cosmological model. Many maps from the middle ages used this model to depict the world and became known as “T” or “T-and-O” maps because of the T-shaped division of land by the Mediterranean Sea and the Nile and Don rivers[viii] (the “O” refers to the world drawn as a circle, as shown in Image 2). Africa replaced term Libya during Roman times[ix] but everything else remained largely unchanged for millennia.

Cracks Starting to Appear

Not everyone accepted this simplified worldview. In the 5th century BCE Herodotus questioned this division and criticised the Greek approach that pursued elegant geometry over accuracy[x]. Strabo wrote in the 1st century BCE that there was much argument about continents with some believing them to be islands while others think of them as mere peninsulas[xi]. He even went further in saying that this system did not take the whole habitable earth into consideration but only their own country and the land exactly opposite[xii]. Despite these discussions, the threefold worldview prevailed. More accurate maps only started to be produced in Europe again in the 14th century when seafaring increased[xiii]. While accurate maps were needed for navigation, the three-part worldview held on until the discovery of the New World by Europeans, which finally made this ancient concept untenable[xiv].

New Models

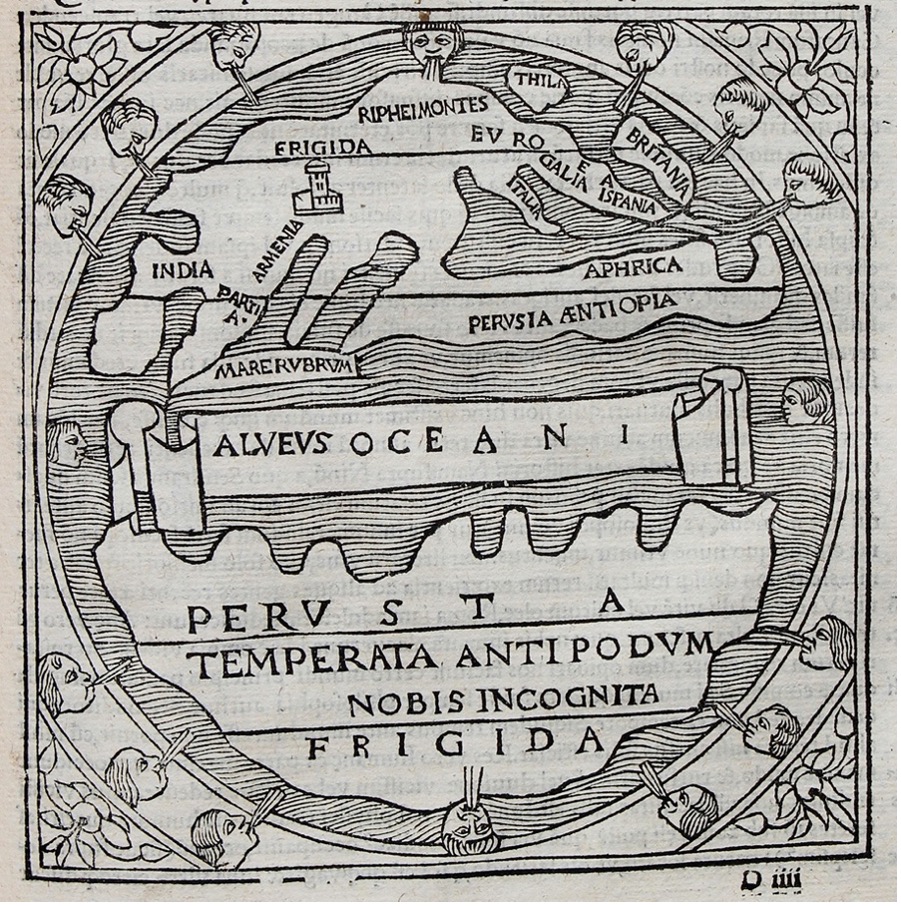

Even after Europeans crossed the Atlantic, the three-continent model did not immediately disappear but caused a significant “cosmographic shock” [xv]. Many European scholars simply ignored all the evidence, while others did not think the New World deserved continent status[xvi]. It took nearly 100 years before the Americas were widely acknowledged as one of the four quarters of the world[xvii]. Once the old conception of all land as a single interconnected Orbis Terrarum—a “world island”—was shattered, and the idea of other inhabited lands—or Orbis Alterius—became accepted, the search for new continents began. A southern continent called Terra Australis was prominent in European thought despite having no evidence of its existence at the time[xviii]. (Shakespeare, for example, makes a character talk about keep time with the Antipodes[xix], i.e. people on the opposite side of the world, in a play that was published six years before Europeans arrived in Australia). When Australia was reached by European explorers, it took even longer to receive continent status. In the meantime, the boundary between Europe and Asia had to be redrawn, followed by deciding where Australia and Asia part. Debates about continent models kept going during the 1800s and early 1900s[xx]. The current seven continent model (with the Americas split into two and Australia replacing Oceania) only became widely accepted in the 1950s[xxi].

European Legacy

The whole concepts of continents is European legacy that can be traced back to ancient Greece. Few other cultures developed a comparable entity. For example, the concept of “Asia” would not have been a meaningful entity by Indian or Chinese standards[xxii]. For them, the world was a continuous mass of land connected in the north with a sea in the south and some offshore islands[xxiii]. For millennia, the Chinese saw themselves as being at the centre of the world but with the spread of Buddhism, its cosmology was adapted by some: There are Chinese Buddhist maps from the early 1600s that depict the island continent with India and its surrounding territories in the shape of an upside-down triangle (with China in the northeast corner rather than at the centre)[xxiv]. A clay tablet from around 700-500 BCE indicates that Babylonians believed in outlying regions called nagu[xxv]but it would be a stretch to compare them to the European concept of continents. While Mesoamerican cultures were prolific mapmakers with highly accurate maps of cities or property lines, larger-scale maps were not topographical in nature but depicted history and their overall cosmology rather than geographical divisions[xxvi]. Widespread acceptance of this view of dividing the world only came once Western thought and scholarism became ubiquitous, not least as a result of European imperialism[xxvii].

Summary

Ancient Greek seafarers described the western shores of their known world as Europe and the eastern ones as Asia. Greek philosophers used this division to create a cosmographic worldview based on elegant geometry. Africa was added (initially as Libya) to form a three-part division of the land, separated by the Mediterranean Sea, and the Nile and Don rivers. The discovery of the New World ultimately shattered this view but it took centuries before it and Australia were accepted as continents. The current model only reached widespread acceptance towards the middle of the 20th century in part as a result of exporting Western thought, as the concept of continents was not common in other cultures.

[i] Whitmarsh, T. (2016, April 08). Bridging the Hellespont. Aeon. URL: https://aeon.co/essays/the-boundary-between-europe-and-asia-is-a-cultural-fiction

[ii] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[iii] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[iv] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[v] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[vi] Harley, J. B., Woodward, D., & Aujac, G. (1987). The foundations of theoretical cartography in archaic and classical Greece (pp. 130-147). In J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.) History of cartography, Volume 1. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

[vii] Dilke, O. A. W. (1987). The culmination of Greek cartography in Ptolemy (pp. 177-200). In J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.) History of cartography, Volume 1. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

[viii] Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2017). Cartography. Encyclopedia Britannica. URL: https://www.britannica.com/science/cartography

[ix] South African History Online. (2019). Africa: What’s in a name? South African History Online. URL: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/africa-whats-name

[x] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[xi] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[xii] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[xiii] Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2017). Cartography. Encyclopedia Britannica. URL: https://www.britannica.com/science/cartography

[xiv] Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2017). Cartography. Encyclopedia Britannica. URL: https://www.britannica.com/science/cartography

[xv] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[xvi] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[xvii] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[xviii] Delaney, J. (2010). Terra Australis. Strait through: Magellan to Cook & the Pacific. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Library. URL: https://lib-dbserver.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/pacific/pacific-ocean/terra-australis.html

[xix] Shakespeare, W. (1600/2009). The Merchant of Venice, 5.1.127-128. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

[xx] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[xxi] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[xxii] Sivin, N., & Ledyard, G. (1992). In J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.) History of cartography, Volume 2, Book 2(pp. 108-136). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

[xxiii] Sivin, N., & Ledyard, G. (1992). In J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.) History of cartography, Volume 2, Book 2(pp. 108-136). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

[xxiv] Yee, C. D. (1994). Traditional Chinese cartography and the myth of westernization. The History of Cartography 2. Pp. 170-202.

[xxv] British Museum. (n.d.). Tablet (Museum number 92687). British Museum. URL: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1882-0714-509

[xxvi] Mundy, B. E. (1998). Mesoamerican cartography. In The history of cartography Vol. 2 Bk. 3: Cartography in the traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific societies. University of Chicago Press.

[xxvii] Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. E. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.